I fail to see the issue with your first issue. It sounds more like a statement than an issue.

For the second issue, you are correct, you do need to assign a point value, even if it is the only assignment in that category. But what you assign to it is completely up to you and since it's the only assignment in that category, the actual point value is mostly irrelevant. I say mostly because I think Canvas rounds grades to 2 decimal places (or maybe it just shows 2 decimals), so if you made it worth 0.01 points, then you would not get the results you wanted.

You may understand that the point value is irrelevant, but your students don't. This is evidenced by your statement about them being upset for every partial point that they "don't earn". There is a psychological aspect at play here that you can use to your benefit. You make that final paper worth 1000 points because it's really important. You can make it worth 1 point so that students don't stress out over it. You can make it worth 100 points so that it looks like a percent and matches your grading scheme (this one has comprehension benefits to the students). The one I like the best for you what you've described so far is to make it worth 20 points because it's worth 20% of the grade. That can be extended to other areas as well -- if your four assignments are worth 25% of the grade, then make them worth 6.25 points each. That is creating an arbitrary point system that is beneficial to the students because it gives them the relative weight in an easy to understand manner.

From a design perspective, though, you cannot display a form with logic like this: If you're using a weighted gradebook and this is the only assignment in the assignment category and you're displaying the grade as a letter grade, then don't ask how many points it's worth. Think about how confusing that would be and how much extra work it would create for the majority of the users. The first time anyone created the first assignment in an assignment group, they would not be asked for the point value. Then, when they create a second assignment in that group, they would have to go back to the first assignment and add the points at that time. My suggestion (in italics) would only go as far as people are willing to "play nice" and are "passing it on because they said they would." But at some point, someone would (to borrow the words of my three year-old) ask "Seriously?" [sorry the inflection doesn't come through in text].

What that means, is that for the few people who have a weighted gradebook and have only one assignment in a group, that you have to put down something, anything (within reason), for the points inside Canvas. However, if you have a category that only has one thing in it, there is a good chance that you probably don't need to use a weighted gradebook in the first place.

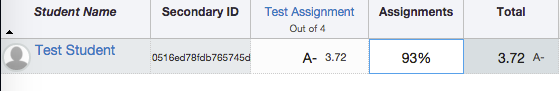

For the third issue, there is good news for your students. When you give a letter grade, Canvas assigns the maximum number of points possible for that letter grade, so there is no partial points that they lose other than what you decide.

Here's an aside about setting up your gradebook. As I was writing about how you could make the final paper worth 20 points because it was worth 20% of the overall grade, some thoughts occurred to me. They may not be directly related to your issue of not wanting to enter a number, but they may benefit other people reading this discussion.

In my experience, students have the most trouble understanding the gradebook when their instructor doesn't understand the gradebook. Although people who "get it" think the gradebook is the simplest thing ever, they need to remember that there are people who, while experts in their area, just don't get the math behind the gradebook. You can sit there and explain it to them and draw it out on paper and they'll leave saying they have it and then next semester, it's messed up again. This is where faculty can benefit from an instructional designer, who can help make sure the gradebook is configured properly. If you don't have an instructional designer, see your Canvas Admin or a knowledgeable colleague and have them double check it. Generally speaking, the more complicated you make it, the more likely you are to screw it up. A messed up gradebook that doesn't match what's in the syllabus, is an invitation for a grade appeal with a good chance of losing.

I cannot count the number of times our Canvas Admin has told me of an instructor who said they can't do a points-based gradebook because the final paper has to be worth 20% of the grade and the four writings have to be worth 25% of the grade, and so on. What they are describing can easily be done with a point-based system. If you take what I described earlier with making the percent match the score on the assignment, then it's super easy and easily understood by the students.

Then there are other instructors who insist "I can't do a weighted gradebook because I have 1000 points, my exams are worth 600 points, homework is worth 200 points, and the final exam is worth 200 points." What they just described was a weighted gradebook -- exams 60%, homework 20%, and final exam 20%. The problem is that they don't understand the math well enough to know that they just described a weighted gradebook.

There are places for both kinds of gradebooks, which is why Canvas offers both. One place a weighted gradebook is beneficial is when you don't know ahead of time how many assignments you will have or how many points each one will be worth. For example, I have participation grades in my statistics class, which may be scheduled or added on the spur of the moment. But I don't want the participation to be more than 5% of the grade no matter how many points go into them. Another place it is beneficial is when you want some assignments to show up in the gradebook but not count towards their final grade -- you can create an assignment group worth 0%. On the flip side, a weighted gradebook is overkill for some classes. In my Finite Math and Differential Equations, I have every assignment mapped out at the beginning of the semester and have manually adjusted the point values on them so that are weighted the way I want them to be weighted and I use a plain non-weighted gradebook.

The two-system gradebook doesn't cover every possible way to do gradebooks. There was an interesting discussion in with one professor sharing how Canvas could not manage his grading system.

However you decide to setup your gradebook, communication is key and if you do a good job of explaining things to students, they get it (for the most part) or you can explain it to them if they don't. Be pro-active and explain things before it becomes an issue and it will help mitigate the problems students have later on. What I would do in your situation is make sure that I tell the students "Canvas requires a point value. It doesn't really matter what the number says, it's the letter grade that's important, but I have to put in a score to get Canvas to recognize the letter grade."

Okay, I wouldn't say that exactly as I have to be intellectually honest with people and the number does matter because an A- of 92% is different than an A- of 90%. I would say something more along the lines of "Grades get in the way of learning, but I have to put something down for you."

I had a thought that "Letter grades are really Likert scales" and as such we should not be assigning point values to them at all. I've long argued that you should not report an average for ordinal data, but that's what people who give a letter grade and then want to convert that into a class grade are doing. Grades work best when you go the other direction - a convenient way of converting numbers into letters so that people can understand them. People who try to assign letter grades without numbers are trying to reverse the table and that is fraught with difficulty. The primary one being that the difference between letter grades is not uniform and that an F includes everything from 0% to 59%, while the others are 10% each. What people who assign letter grades instead of numbers are are trying to do is take a letter that represents a range of values and find the average of those. We talk about grouped data and frequency tables with classes in statistics. We found averages of those, but the best we could do would be to use the middle of the interval since we had no idea whether most of the values were at the top, the middle, the bottom, or spread evenly throughout. Canvas assigns the top of the interval, giving the benefit of the doubt to the student. That was the argument made in .

That throwing away precision by assigning only a letter grade is an issue of significant figures. The idea of significant figures revolves around the notion that you cannot report accuracy or precision in a final answer when it wasn't there in the initial measurement. That loss of significant figures by assigning only a letter grade cannot be recovered later on. Now, that may be acceptable, maybe you don't have the resolution to distinguish between an 95% A and a 94% A, so you just call it an A. When I grade papers, I can do that, even subjectively, because I say "This is a B paper, but it's better than this other group's B paper." But it isn't really accurate to blame points for why students are complaining about partial credit. You're doing that when you assign a B- instead of a B.

Again, much of the problems can be eliminated if you understand what you're trying to accomplish, make sure the gradebook accurately reflects that, and you communicate any potential issues to your students.

This discussion post is outdated and has been archived. Please use the Community question forums and official documentation for the most current and accurate information.